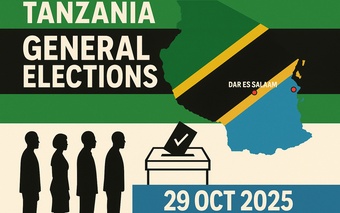

On 29 October 2025, Tanzania will

hold its general elections to elect the President, members of the National

Assembly, and local ward councillors.

The ruling party, Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), which has held power in one form

or another since independence in 1961, is widely expected to extend its

long-standing dominance

On paper, the election offers

Tanzanians an opportunity to articulate their voices through the ballot, but in

practice, the environment presents significant structural hurdles: major

opposition figures are barred, leading parties are excluded, and concerns about

fairness are widespread.

These dynamics raise fundamental

questions about the quality of electoral competition and what the outcome means

for governance, legitimacy and long-term national development.

At the centre of the contest is Samia Suluhu Hassan, Tanzania’s first female head of

state and the CCM’s candidate. She assumed office in 2021 following the death

of her predecessor and now seeks democratic endorsement. However, several of

her key opposition rivals are either banned or in detention. For example, Tundu

Lissu, a high-profile opposition figure and former challenger, is jailed on

treason charges. The main opposition party, Chama Cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo

(CHADEMA) was disqualified for failing to sign a required code of conduct.

Thus, while the ballot formally

lists multiple contenders (some 16 other presidential hopefuls according to

official data), the degree of real competition appears minimal. Analysts

suggest that with the two largest opposition parties either excluded or

suppressed, the outcome is all but predetermined, raising concerns about the

authenticity of voter choice.

A number of critical issues are

informing Tanzanian public sentiment ahead of the vote. Economically, Tanzania

has performed relatively well compared to some regional peers, with resilient

growth, lower external debt risk, and stable inflation often cited. But

political freedom and democratic space are seen to be narrowing. Reports of

opposition suppression, enforced disappearances, and restricted civic space

have raised alarms among human rights groups and democratic watchers.

Voter apathy is another concern.

With the outcome viewed as foregone and meaningful competition constrained,

many young people and rural voters are disengaged. Some observers warn that low

turnout may further erode the election’s legitimacy. Additionally, the possibility of internet or

social media restrictions on election day has been raised, which could dampen

transparency and citizen monitoring.

From an international standpoint,

the 2025 Tanzanian elections are receiving scrutiny. Organisations such as

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have cautioned that the process

risks becoming “procedural” rather than meaningful, pointing to structural

biases detrimental to genuine choice. Analysts argue that much of Tanzania’s

future development hinges not only on economic indicators but on strengthening

accountability and civic space.

In a broader East African and

African context, the outcome has ramifications for debates around multi-party

democracy, regional stability, and how long-standing ruling parties can adapt

to changing demographics and demands.

Take Voters' Compass

Take Voters' Compass